Before the wells run dry we should know the story.

Dramatic shifts are underway around the world and communities are having trouble keeping up. The reality is none of us are keeping up and they are just the first to feel and see and impacts of these dramatic changes.

Photo: Daisy Carlson

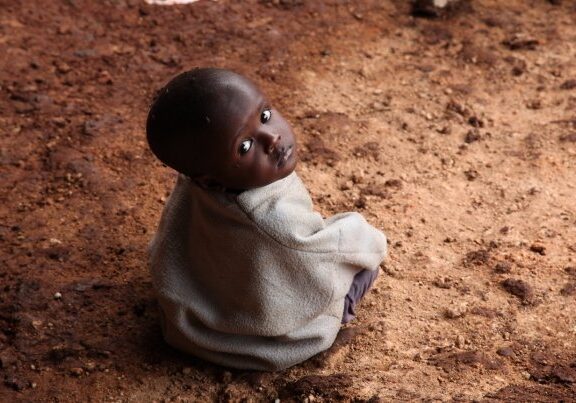

Four Children

Future generations, the children and animals who do not have a vote, what are we doing to protect them from the ravages of climate change and the resulting conflicts arising for land, water, property and the distribution of prosperity and education. What are our responsibilities as global citizens, as politicians, as parents.

Article and Photo: Daisy Carlson

Four Solutions

Rotational grazing, a sustainable livestock management practice, offers several solutions in mitigating CO2 and contributing to overall environmental sustainability. Here are four key ways in which rotational grazing can help reduce carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions:

Improved Soil Carbon Sequestration: Rotational grazing involves periodically moving livestock to different grazing areas, allowing previously grazed pastures to recover. This rest period encourages the growth of grasses and other vegetation, which in turn promotes greater carbon sequestration in the soil. Healthy grasslands can store significant amounts of carbon in their roots and soil, thereby reducing the release of CO2 into the atmosphere.

Reduced Methane Emissions: Rotational grazing practices often result in lower livestock stocking densities and more controlled grazing patterns. This can lead to a reduction in enteric methane emissions, a potent greenhouse gas produced during digestion in the stomachs of ruminant animals. By spreading out grazing and ensuring that animals do not overgraze, rotational grazing can help mitigate methane emissions from livestock.

Preservation of Ecosystems: Properly managed rotational grazing helps maintain the health and biodiversity of ecosystems. When ecosystems are healthy and diverse, they are better equipped to function efficiently, including the capacity to absorb and store carbon. Protecting and restoring native vegetation within grazing systems can further enhance the ecosystem's ability to sequester carbon and reduce CO2 emissions.

Enhanced Pasture Productivity: Rotational grazing can lead to more productive pastures over time. As pastures become more productive, they can support larger populations of livestock, potentially reducing the need to clear additional land for agriculture or grazing. This can help curb deforestation and land-use changes that release CO2 into the atmosphere.

Traditional pastoral cultures may help us gain a better understandning of best practices for rotational grazing. How this contribute to reducing greenhouse gas emissions, soil health and water retention will depend on our understanding and management of these practices. Nevertheless this is an important part of a broader strategy to combat climate change. Offset partnerships

Article and Photo: Daisy Carlson

Four Elements

Earth, Air, Water, Metal. Can culture and technology keep up with a changing climate? What do pastoral cultures have to teach us about preserving climate and land? Traditional rotational grazing practices and age-old traditions of nomadic herders offer valuable insights that can inform our efforts to address climate change. As they struggle to adapt they share some key lessons from their time-tested practices.

Article: Daisy Carlson

Earth, Air, Water, and Metal—the fundamental components of our existence—have forged the foundation upon which humanity has thrived. But now, this intricate equilibrium is under siege, threatened by the profound shifts brought about by a changing climate.

In the face of this existential challenge, a symphony of human creativity, innovation, and determination emerges. Culture and technology, often the architects of our progress, stand at a crossroads. Can they adapt swiftly enough to align with the shifting cadence of the Earth's natural systems? It is a question that reverberates across the globe.

We embark on a journey to explore the intricate challenges and responses of pastoral cultures to this monumental shift. From the Arctic to the equator, from rocky cliffs to the Savanahs, Four Pastures ventures into the lives of those on the front line of adaptation. Herders, Scientists, and Artists capture the beauty and vulnerability of our changing landscapes, illuminating the intricate human connection to the Earth's elements.

Tribal wisdom and resolve will determine whether culture and technology can indeed keep pace with a changing climate—a challenge that is not merely environmental but also cultural, economic, and moral. Together, let us explore stories of hope and resilience, where balance is restored amid the elements of change.

Alaska

In the northernmost reaches of our planet, in a place where the cold has always reigned supreme, an unsettling transformation is underway. Barrow, Alaska, a land where the cycles of nature have been as dependable as the ticking of a clock, is now experiencing a deviation of epic proportions. As the climate warms hunting communities are forced to change age old methods of food storage. Thethe anxieties of our warming world is rapidly changing Alaskan indigenous culture, melting permafrost, and the relentless specter of greenhouse gases give the global community pause.

The epicenter of this unfolding drama is the permafrost, a vast expanse of frozen ground spanning 8.8 million acres. For millennia, it has served as an icy vault, locking away the secrets of bygone epochs, preserving ancient life, and holding within its icy grasp a chilling reminder of Earth's history. But now, this Arctic sanctuary is beginning to melt, and as it does, it sets in motion a chain reaction that could reshape our understanding of climate change.

Hidden within the permafrost are trillions of microbes, ancient survivors of a long-forgotten era. They've slumbered for eons, encased in the frozen embrace of the Arctic tundra. Yet, as the temperature rises, their icy prison begins to thaw, releasing them into a world unprepared for their awakening.

What these long-dormant microbes bring with them is a potent cocktail of methane and carbon dioxide, two of the most notorious greenhouse gases. Methane, in particular, is a climate culprit of staggering proportions. It possesses the capacity to trap heat in the atmosphere a hundred times more effectively than carbon dioxide, a fact that has long sent shivers down the spines of climate scientists.

Until now, methane had been a relatively minor player in the grand theater of greenhouse gases, accounting for a mere 10% of the atmospheric burden. But as the permafrost melts and the ancient microbes stir, that equation may be changing. With each methane molecule released into the atmosphere, the Earth's already precarious balance is further destabilized.

This is the essence of our new climate reality, a reality where even the most remote corners of the Earth are not immune to the consequences of our actions. Barrow, Alaska, with its melting permafrost and the ancient, methane-laden ghosts it harbors, serves as both a cautionary tale and a harbinger of things to come.

The story of Barrow is a reminder that the climate crisis is not a distant specter but a palpable, unfolding drama. It underscores the interconnectedness of our planet's systems and the urgency of our response. As we grapple with the consequences of our warming world, we are confronted with the unsettling truth that even the most obscure corners of our Earth can send ripples of change throughout the entire climate system. The cycle of nature in Barrow may have been thrown off course, but its message is clear: the time for action is now, before the equation tips further out of balance.

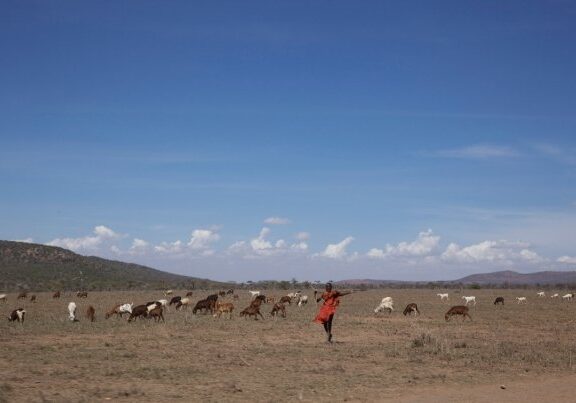

Kenya

Nomadic herders have long practiced sustainable land management by moving their livestock across grazing areas in a rotational manner. This prevents overgrazing, allows grasslands to regenerate, and maintains soil health. Emulating these practices can help combat deforestation and land degradation, which are significant contributors to greenhouse gas emissions.

Nomadic herders often rely on diverse herds of animals. This promotes biodiversity by preventing the dominance of a single species, which can be detrimental to ecosystems. In the context of climate change, preserving biodiversity is crucial for resilience and adaptation to shifting environmental conditions.

Traditional grazing practices involve smaller herds and lower animal densities, which can reduce methane emissions from livestock. Methane is a potent greenhouse gas, and by adopting more extensive grazing practices, we can mitigate its impact on climate change. Herds Tone and fertilize the soil to improve soil health, water retention and biodiversity.

Nomadic herders have a deep understanding of their local environments and ecosystems, which has allowed them to adapt to changing climatic conditions over generations. Incorporating this indigenous knowledge into modern climate adaptation strategies can enhance their effectiveness.

Traditional herding practices often emphasize communal ownership and cooperation among herders. This sense of community can be instrumental in building resilience to climate change, as communities come together to share resources, knowledge, and strategies for coping with environmental challenges.

Many traditional grazing practices rely on low-tech and low-cost methods. These approaches can be accessible to communities in developing regions, providing effective climate solutions that don't require extensive financial investments.

Properly managed grasslands and savannas can act as significant carbon sinks, sequestering carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Rotational grazing practices can help maintain and enhance these natural carbon storage systems.

Incorporating these lessons into modern agricultural and land management practices can contribute to climate change mitigation and adaptation efforts. By blending traditional wisdom with modern science and technology, we can develop sustainable and climate-resilient agricultural systems that benefit both the environment and the communities that rely on them. Moreover, respecting and valuing the knowledge of nomadic herders and indigenous peoples is an essential part of building a more inclusive and equitable response to climate change.

Article and Photo: Daisy Carlson

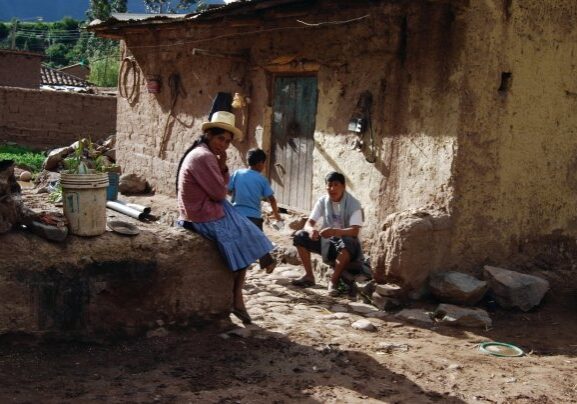

Andes

it is easy to understand why Andean people have long worshiped the elements that allow them to survive in this harsh climate. The people of the Andes may live at more than 15,000 feet above sea level. Now a cultural shift is underway for the herdsman of the region. Pastoral communities are adjusting their livestock grazing patterns in response to changing weather conditions, moving their herds to higher elevations during warmer months and lower elevations during colder months to ensure access to grazing areas and minimize the impact of extreme weather events and climate change. While governments seek technical solutions to climate-related problems, Quechua-speaking farmers in the Andes are struggling to understand events that are altering their livelihood. Indigenous and traditional knowledge systems play a crucial role in adapting to climate change. Communities are drawing on their ancestral wisdom to predict weather patterns and make informed decisions about when to plant, harvest, or move their herds.

Article: Scientific America

Photo: Daisy Carlson

Mongolia

Mongolia "In the past, the country experienced widespread dzud about once in a decade, but they have recently been occurring every few years. Experts say the rising frequency is due to a combination of climate change and human activity, which has increased the size of herds to levels the grasslands cannot sustain." The Guardian

A dzud is a natural disaster in Mongolia, typically characterized by a harsh winter following a summer drought. During a dzud, extremely cold temperatures and heavy snowfall can lead to a shortage of food and water for livestock, which is a significant concern in Mongolia, where many rural livelihoods depend on herding animals like sheep, goats, cattle, and horses.

The term "dzud" is of Mongolian origin and refers to a particularly severe winter weather event. These events can have devastating consequences for both livestock and herders. Livestock may struggle to find food beneath the deep snow, leading to starvation and a significant loss of animals. Herders may face economic hardship and food shortages as a result.

Dzuds are not uncommon in Mongolia, but their frequency and severity have increased in recent years, which is often attributed to climate change and changing weather patterns. These events highlight the vulnerability of traditional nomadic herding communities in the face of climate-related challenges. Efforts are ongoing to find ways to mitigate the impacts of dzuds and build resilience among affected communities.

Article: Daisy Carlson

Photo: By photographer and livestock herder S.Tsengelbayar from Xilingol

Share your story

Do you have a story to tell about the land and climate change somewhere in the world. Share it at Four Pastures so we can see the world together.